At the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month. At this time of year, in Britain, there are an awful lot of poppies in evidence on the coats and jackets of the great and the good. Also on many of the not so great. Possibly, too, many of the less than good.

In Flanders Fields

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.

This is the beginning of a poem by Canadian soldier and medical officer John McCrae. It was written in May 1915, soon after he had conducted the burial of a fellow soldier killed during the Second Battle of Ypres (April-May 1915). He was, no doubt, expecting the arrival of more wounded at the field hospital he commanded. Anticipating also there would soon be more graves. It captures some commonly observed sights in war-torn Belgium: the sunset, the larks, the fields of flowering poppies.

Wikipedia says Due to the extent of ground disturbance in warfare during World War I, corn poppies bloomed between the trench lines and no man’s lands on the Western front. I’m no gardener, but this seems reasonable. Still, there’s no supporting reference. I found some corroboration on a seed and gardening website. Wildseed.co.uk says poppy seeds can lie dormant for decades waiting for a suitable opening … so it was around the battlefields of the Western Front that poppies sprung up and bloomed in profusion in a landscape cultivated not by ploughs but on soil laid bare by explosive shells and mines.

Becoming symbolic

John McCrae wasn’t alone as a soldier on the Western Front in observing how some aspects of nature carried on regardless, despite the carnage. The poems of the war poets and soldiers’ memoirs are scattered with similar references. The poppies, the larks, the sunset. Nature’s indifference to man’s concerns, once observed, may become symbolic.

McCrae’s poem was a big hit, published first in Punch in Britain, then elsewhere, translated, anthologised and quoted. No doubt the final verse helped things along.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

Phrases from this verse were co-opted into propaganda and recruitment posters. The command of the dead to Take up our quarrel with the foe, for example, seems to have figured in an election in Canada during the war. (Something of which McCrae approved.)

To you from failing hands we throw / The torch… inspired more than one response. We caught the torch you threw / And holding high, we keep the Faith…

And then there’s that implied threat: if you don’t fight on We shall not sleep but come back and haunt you. It’s no wonder that for a period at least the last verse was often left out when the poem was re-printed.

The Poppy Appeal

At the very end of the war an American academic, Moina Michael, inspired by “Flanders Fields”, took to wearing a red poppy to commemorate the war dead. (She’s the one who wrote We caught the torch… above.) She managed to persuade American and, with the help of Frenchwoman Anna Guérin, French and British people to adopt the poppy as a symbol of remembrance and, more importantly, as an an object to be made and sold to draw in funds for war veterans.

This was sadly needed. Many soldiers died in the war. One estimate puts the British Empire dead at a little under 10 million soldiers. But twice that number, about 20 million, survived with wounds of various degrees of seriousness. Charitable organisations – in Britain Field Marshal Lord Haig’s British Legion (later the Royal British Legion) – took up Michael’s idea of making and selling poppies. They are still doing it today.

The symbolism of the poppy

The Royal British Legion’s website has several pages given over to the history of the Poppy Appeal and the symbolism of the poppies. Among others, this page goes out of its way to tell visitors that the poppy is…

- A symbol of Remembrance and hope

- Worn by millions of people

- Red because of the natural colour of field poppies

And that it is not…

- A symbol of death or a sign of support for war

- A reflection of politics or religion

- Red to reflect the colour of blood

I think they protest too much.

Yes, the poppies are a symbol of remembrance, but hope? For what? For an end to war perhaps? But the Royal British Legion doesn’t make a great effort to link its poppies to the wastefulness and horror of war.

On another page I read: The First World War is infamous for the number of lives it cost, however … [i]t also laid the foundations of British Remembrance… So WW1 is a good thing because it gave us something to remember?

And on the current front page: The Royal British Legion led the nation in saying Thank You to the First World War generation, all who served, sacrificed and changed our world.

So, let’s wear poppies to say thank you to The Dead for taking up the quarrel with the foe?

Social pressure

And yes, poppies are worn by millions every year. In Britain at least the social pressure on people who choose not to wear one is very heavy. The Royal British Legion may not want that to be a reflection of politics and religion, but it feels an awful lot as though it is. Especially when you see the British establishment, poppy-decorated and out in force.

In 2015 the BBC ran an article: Five reasons people don’t wear poppies. It bears re-reading. (And here’s a BBC video clip on the same subject from 2018.)

And of course the poppy is a symbol of death. I don’t think McCrae intended that in his poem. Not at all. In “In Flanders Fields” the living poppies are contrasted with the crosses marking the graves of the dead. The poppies blow / Between the crosses… But here we are, 103 years on and everyone involved in the First World War is now dead. Whatever the Royal British Legion wants the poppies to mean, those who wear them are very likely thinking about dead people. So, like it or not, that’s part of what they symbolise.

Finally, yes, field poppies are red. As red as blood. You can’t divorce the colour from the notion of blood just because you find it distasteful.

White poppies

Of course one might choose to wear a white poppy. They’re mentioned as an option in that BBC article. All these criticisms of the red Royal British Legion poppies were already current early on. In 1933 the Co-operative Women’s Guild started producing white poppies as an alternative symbol of remembrance. These were intended to commemorate all the dead in all wars. Not just the British dead, not just the military dead. Nowadays white poppies are produced and sold by the Peace Pledge Union.

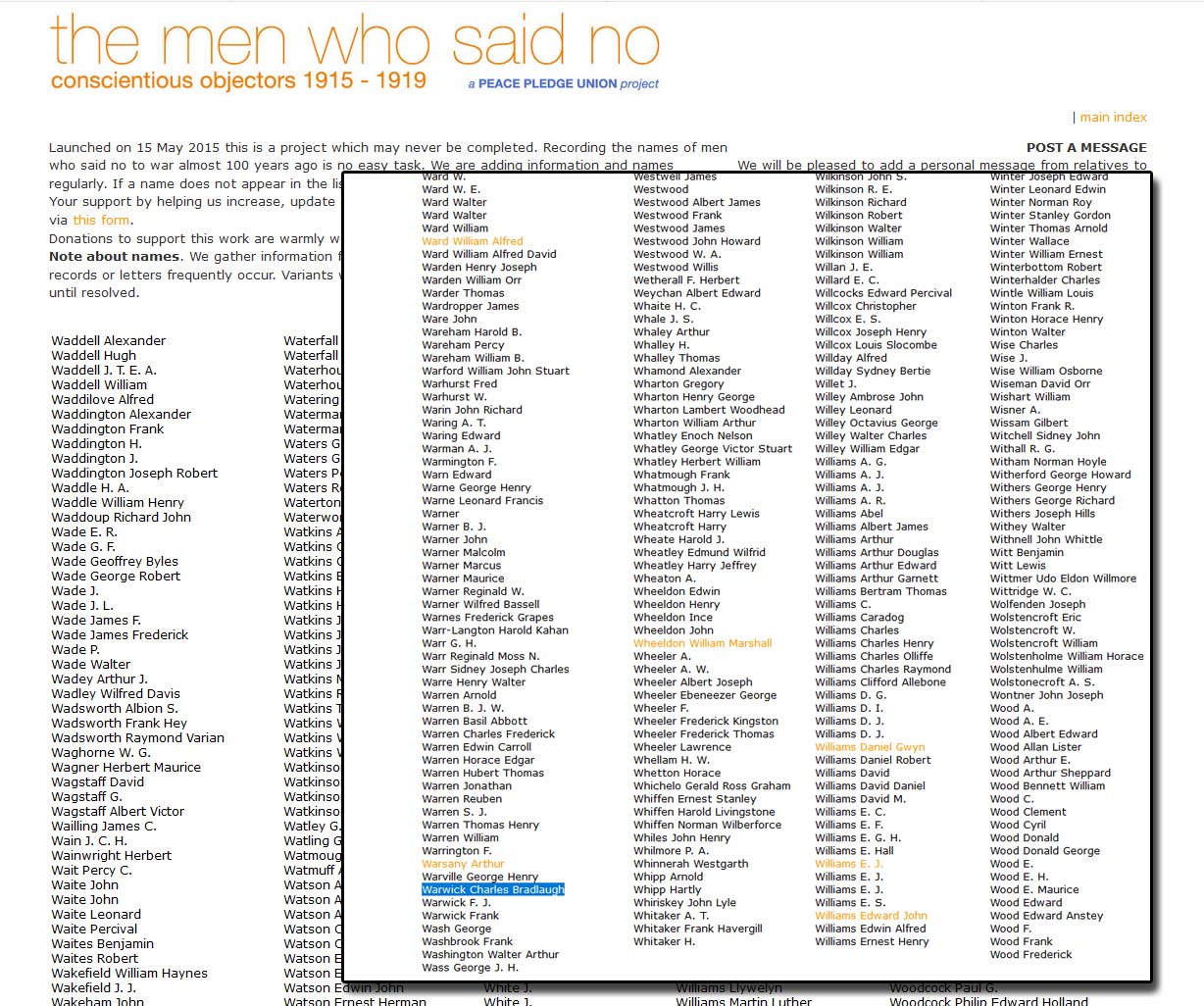

Perhaps in the wake of all the business of WW1 commemoration the PPU’s website includes a link to another website, The Men Who Said No. This site sets out to list the First World War’s British Conscientious Objectors. The COs were the men, called up to the military during the latter part of WW1, who refused to fight.

Charlie B

There were 20,000 or so. Looking through the list I was rather pleased to find my maternal grandfather’s name: Charles Bradlaugh Warwick. It adds weight to family stories. Mind you, I think his reasons for objecting to the war were rather different from reasons I might have had. He was no pacifist and his objections were entirely ideological. (This is the man who later embarrassed my grandmother, some time in 1922, by standing up in at a public meeting in Manchester’s Free Trade Hall. He introduced himself with I am a Communist, before asking a question in a debate. Charlie was also, the family bibliomaniac.)

I feel I should add that I’ve been struggling to find a way to write about this since Sunday. Since Remembrance Day in fact. I broke out all my war poetry books and a couple of books of memoirs and then spent an inordinate amount of time on-line. I started twice and twice threw away what I’d written as tosh. The above may be open to the same criticism, but I’ll let it stand. At least it’s better than the earlier drafts.

Illustration credits and notes

- Header image: collage of still photos taken from the TV, from a variety of video news reports in the period around early November 2018 .

- Illustrations of Poppies in Flanders Fields from Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Poppies_Field_in_Flanders.jpgIllustrations advertising Victory Bonds from Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:If_Ye_Break_Faith_-_Victory_bonds_poster.jpg

- Illustration of modern Poppy Appeal poppy cropped from Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Soldier_With_Poppy_MOD_45150461.jpg

- The illustration of Queen Elizabeth II with her spray of poppies broach is made from a still photo taken of a TV screen. News film footage of the 2018 Remembrance Day at the Cenotaph in Whitehall, London.

- The illustration of Charlie B’s name in the list of COs is made from two screen captures from the website of The Men Who Said No at http://menwhosaidno.org/men/menlist/w.html

I’m also publishing this article for the #Blogg52 challenge.

Oerhört intressant. Jag har alltid undrat varför engelsmännen bär de röda pappersblommorna. Tack!

Kram Kim

Och nu vet du det! 🙂